ความเข้าใจผิดระหว่าง “ไม้อ่อน” กับ “อ่อนข้อ” ต่อกัมพูชา กับทางเลือกเชิงยุทธศาสตร์ ของนายกฯ แพทองธาร

#อัษฎางค์ยมนาค #อ่านเกมอำนาจ #ตอบโต้เขมร

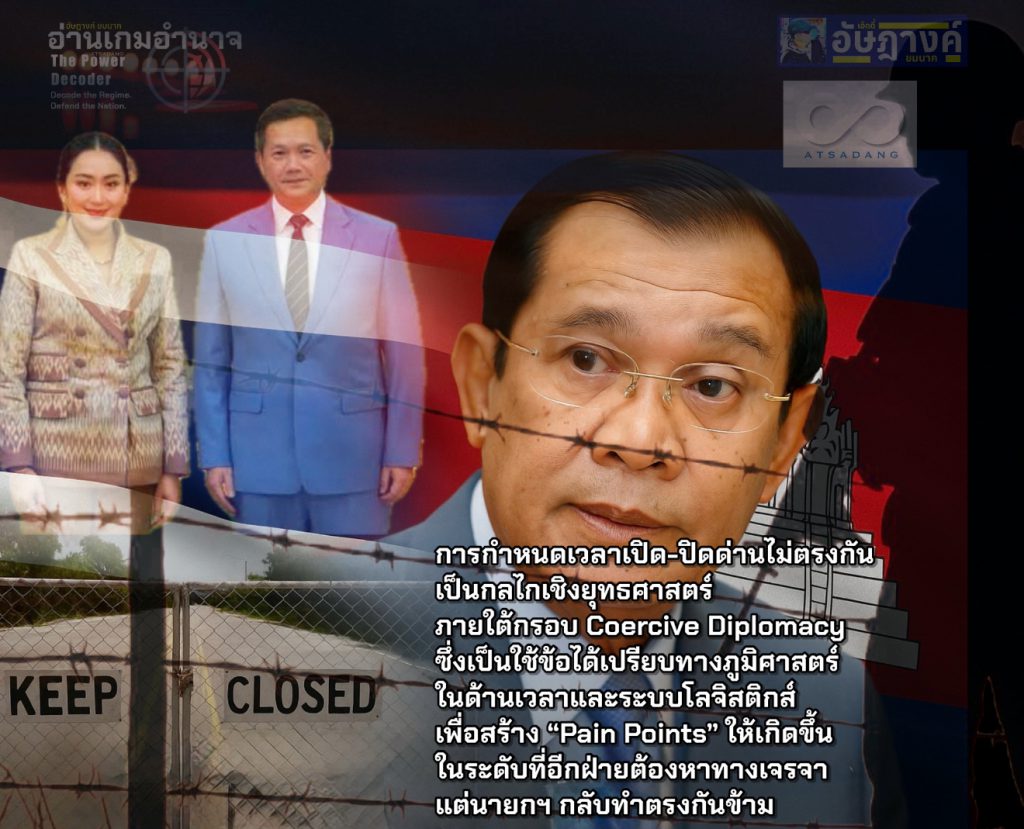

การกำหนดเวลาเปิด-ปิดด่านไม่ตรงกัน เป็นกลไกเชิงยุทธศาสตร์ภายใต้กรอบ Coercive Diplomacy ซึ่งเป็นการใช้ข้อได้เปรียบทางภูมิศาสตร์ ในด้านเวลาและระบบโลจิสติกส์เพื่อสร้าง “Pain Points” ให้เกิดขึ้นในระดับที่อีกฝ่ายต้องหาทางเจรจา

แต่นายกฯ กลับทำตรงกันข้าม

ความไม่พอใจของคนไทยต่อมาตรการ “ตั้งรับ” และเสียงเรียกร้องให้ใช้ “ไม้แข็ง” กับกัมพูชา สะท้อนความรู้สึกชาตินิยมและห่วงใยต่อศักดิ์ศรีอธิปไตย ซึ่งเป็นปฏิกิริยาที่พบได้ทั่วไปในสถานการณ์พิพาทชายแดน อย่างไรก็ตาม การตัดสินใจใช้มาตรการแข็งกร้าวหรือไม่ ควรตั้งอยู่บนฐานของยุทธศาสตร์ชาติ ผลประโยชน์ระยะยาว และผลกระทบที่อาจตามมาในหลากหลายมิติ

ในทางรัฐศาสตร์และยุทธศาสตร์ความมั่นคง การเลือกใช้มาตรการที่ไม่รุนแรง แต่มีผลต่อพฤติกรรมของรัฐคู่ขัดแย้งนั้น เข้าข่ายแนวคิด “Coercive Diplomacy” หรือ “การทูตแบบกดดัน” (George, 1991) ซึ่งหมายถึง การใช้อิทธิพลทางเศรษฐกิจ การทหาร หรือโครงสร้าง เพื่อกดดันให้อีกฝ่ายเปลี่ยนพฤติกรรม โดยไม่ต้องใช้กำลังทหารโดยตรง

การกำหนดเวลาเปิด-ปิดไม่ตรงกันคือเครื่องมือที่ไทยใช้ในระดับ “พอเหมาะ” เพื่อกดดันอีกฝ่ายโดยไม่ยกระดับความขัดแย้ง เป็นการรักษาความได้เปรียบของไทยในสถานการณ์พิพาท ซึ่งเป็นกลไกเชิงยุทธศาสตร์ภายใต้กรอบ Coercive Diplomacy

แต่ข้อเสนอของนายกรัฐมนตรีในการให้เวลาเปิด-ปิดด่านตรงกันกับกัมพูชา อาจทำให้ไทยสูญเสียเครื่องมือต่อรองสำคัญ ที่เป็นความได้เปรียบของไทย ในช่วงเวลาที่จำเป็นต้องรักษาอำนาจและเสถียรภาพเชิงยุทธศาสตร์

ทำไมนายกฯ จึงเสนอแนวทางที่ทำให้ไทยเสียโอกาสอย่างนั้น

คำตอบอาจจะเป็น…ความเข้าใจผิดระหว่าง “ไม้อ่อน” กับ “อ่อนข้อ”

รัฐบาลปัจจุบันมีแนวโน้มใช้นโยบาย “Soft Foreign Policy” ที่ให้ความสำคัญกับความร่วมมือและบรรยากาศที่ดีระหว่างประเทศ มากกว่าการรักษา “เครื่องมือกดดัน” ตามแนวคิดของ Coercive Diplomacy ซึ่งอาจเกิดจากความไม่เข้าใจว่าการกดดันเชิงยุทธศาสตร์ไม่ใช่การสร้างความขัดแย้ง แต่คือ การรักษาอำนาจต่อรองโดยไม่ใช้กำลัง

การยอมถอดเครื่องมือกดดันโดยไม่มีการแลกเปลี่ยน (concession) จากอีกฝ่าย อาจสะท้อนการขาดความเข้าใจในหลัก “Reciprocity” ของการทูตเชิงอำนาจ

การยอมถอยจากจุดได้เปรียบทางยุทธศาสตร์เท่ากับ ยอมลดอำนาจต่อรองลงโดยไม่จำเป็น และการทำให้เครื่องมือแบบ Coercive Diplomacy กลายเป็น “symbolic concession” (การยอมแพ้เชิงสัญลักษณ์) ยิ่งทำให้ฝ่ายตรงข้ามได้ใจ

หรืออาจเป็นไปได้ว่า นายกรัฐมนตรีต้องการส่งสัญญาณเชิงสัญลักษณ์ต่อกลุ่มภายในประเทศ ซึ่งเป็นกลุ่มผลประโยชน์ที่ได้ประโยชน์จากการค้าชายแดน ซึ่งแฝงอยู่เบื้องหลังการตัดสินใจ หรือไม่?

กลไกเช่นนี้สามารถอธิบายได้ด้วยแนวคิดของ Robert Putnam (1988) ว่า “นโยบายต่างประเทศ” มักถูกกำหนดจากแรงกดดันของ “การเมืองภายใน”

อย่างไรก็ตาม การตัดสินใจใช้มาตรการไม้แข็ง หรือยุทธศาสตร์ที่เหมาะสมด้วยการตั้งรับอย่างมีชั้นเชิง ควรตั้งอยู่บนฐานของผลประโยชน์ระยะยาว และผลกระทบที่อาจตามมาในหลากหลายมิติ

▍ ข้อดีของการใช้มาตรการแข็งกร้าว

• เพิ่มอำนาจต่อรองในการเจรจา: มาตรการเช่น การจำกัดการค้าชายแดน การชะลอความร่วมมือ การจำกัดไฟฟ้าและอินเทอร์เน็ต สามารถกดดันกัมพูชาให้กลับเข้าสู่โต๊ะเจรจาด้วยท่าทีที่ประนีประนอมมากขึ้น

• สะท้อนจุดยืนปกป้องอธิปไตย: แสดงให้ประชาชนเห็นว่ารัฐบาลมีท่าทีเข้มแข็ง ไม่เพิกเฉยต่อภัยคุกคาม

• ใช้จุดได้เปรียบของไทย: โดยเฉพาะด้านพลังงาน สินค้า และแรงงาน ที่กัมพูชายังพึ่งพาไทยในหลายมิติ

▍ข้อจำกัดและความเสี่ยงของมาตรการแข็งกร้าว

• การตอบโต้แบบตาต่อตา: เช่น การปิดด่านชายแดน การนำเรื่องเข้าสู่เวทีระหว่างประเทศ หรือการปลุกกระแสชาตินิยมในกัมพูชาเอง

• ผลกระทบต่อประชาชนและเศรษฐกิจชายแดน: โดยเฉพาะกลุ่มที่พึ่งพาการค้าข้ามแดนและแรงงาน

• ความเสี่ยงด้านภาพลักษณ์ในเวทีระหว่างประเทศ: หากมาตรการของไทยถูกตีความว่าใช้อำนาจเกินขอบเขต หรือขัดหลักสันติวิธี

• ผลสะท้อนทางการเมืองภายใน: ฝ่ายตรงข้ามอาจนำมาใช้เป็นประเด็นโจมตีรัฐบาลว่าทำให้สถานการณ์เลวร้ายลงหรือขาดวิจารณญาณเชิงยุทธศาสตร์

▍ยุทธศาสตร์ที่เหมาะสม: ตั้งรับอย่างมีชั้นเชิง

แม้จะมีแรงกดดันให้ใช้ “ไม้แข็ง” แต่ผู้เชี่ยวชาญส่วนใหญ่เห็นตรงกันว่า ไทยควรยึดยุทธศาสตร์ “ตั้งรับอย่างมีชั้นเชิง” โดยเน้นเจรจาและกลไกทวิภาคีควบคู่กับการเตรียมมาตรการตอบโต้ไว้รองรับ หากสถานการณ์ยกระดับอย่างไม่พึงประสงค์

▍ การใช้มาตรการแข็งกร้าว “ในระดับที่พอเหมาะ” คืออะไร?

“พอเหมาะ” ในบริบทนี้ หมายถึง การใช้มาตรการที่มีความเข้มข้นเท่าที่จำเป็น เพื่อลดแรงเสียดทาน ขณะเดียวกันก็รักษาอำนาจต่อรอง และไม่ปล่อยให้อีกฝ่ายได้เปรียบหรือยกระดับความขัดแย้งเกินควบคุม

▍ ลักษณะของมาตรการ “พอเหมาะ” ได้แก่:

• มีเป้าหมายชัดเจน: มุ่งยับยั้งการละเมิด ไม่ใช่เพื่อระบายอารมณ์หรือสร้างภาพทางการเมือง

• เลือกใช้เฉพาะจุดที่ได้เปรียบ: เช่น การจำกัดการค้าบางหมวด การตรวจสอบเข้มงวด การชะลอโครงการบางประเภท

• มีความยืดหยุ่น: พร้อมถอยหรือผ่อนคลายเมื่อมีสัญญาณเชิงบวกจากอีกฝ่าย

• หลีกเลี่ยงการกระทบประชาชนโดยตรง: ไม่ควรใช้มาตรการที่ทำลายความสัมพันธ์ระยะยาวหรือสร้างความเสียหายต่อประชาชนทั้งสองประเทศ

• สื่อสารอย่างมีชั้นเชิง: ใช้การเจรจาเงียบ การทูตเบื้องหลัง และการส่งสัญญาณที่มีประสิทธิภาพในเวทีระหว่างประเทศ

▍ ตัวอย่างมาตรการ “พอเหมาะ”:

• การจำกัดเวลาการเปิด-ปิดจุดผ่านแดน

• การตรวจสอบสินค้าข้ามแดนอย่างเข้มงวด

• การจำกัดวีซ่าชั่วคราว

• การชะลอหรือระงับความร่วมมือชายแดนบางโครงการ

• การส่งสัญญาณพร้อมเจรจาและเงื่อนไขการกลับสู่ความร่วมมือ

▍ข้อขัดแย้งเชิงนโยบาย: เวลาเปิด-ปิดด่านชายแดนกับกัมพูชา

จากข้อมูลล่าสุด นางสาวแพทองธาร ชินวัตร นายกรัฐมนตรี ได้ลงพื้นที่ชายแดนและเสนอแนวคิดให้ ประสานเวลาเปิด-ปิดด่านชายแดนให้ตรงกับฝั่งกัมพูชา โดยให้เหตุผลว่า จะช่วยอำนวยความสะดวกให้แก่ประชาชนและส่งเสริมการค้าระหว่างประเทศเพื่อนบ้าน

อย่างไรก็ตาม ข้อเสนอดังกล่าวขัดกับแนวทางของฝ่ายความมั่นคงและผู้ปฏิบัติในพื้นที่ ซึ่งยืนยันว่า การกำหนดเวลาเปิด-ปิดด่านให้ “ไม่ตรงกัน” มีนัยทางยุทธศาสตร์ เป็นมาตรการเชิงกดดันที่ไทยใช้เพื่อสร้างอำนาจต่อรองกับกัมพูชา โดยเฉพาะในช่วงที่มีข้อพิพาทหรือความตึงเครียดบริเวณชายแดน

▍วิเคราะห์ตามหลัก “มาตรการแข็งกร้าวที่พอเหมาะ”

มาตรการแข็งกร้าวที่ “พอเหมาะ” หมายถึง การใช้กลไกกดดันเฉพาะจุดที่ไทยได้เปรียบ เช่น การ ควบคุมเวลาเปิด-ปิดด่านให้ไม่ตรงกัน เพื่อสร้างความไม่สะดวกให้กับอีกฝ่ายอย่างพอประมาณ โดยไม่ยกระดับความขัดแย้ง และไม่กระทบต่อประชาชนอย่างรุนแรง

แนวทางนี้มีเป้าหมายชัดเจน คือ ใช้ความได้เปรียบเชิงภูมิศาสตร์และโครงสร้างพื้นฐานของไทยในฐานะประเทศที่มีอำนาจควบคุมฝั่งชายแดน เพื่อกดดันกัมพูชาให้อยู่ในกรอบเจรจา โดยไม่ต้องใช้มาตรการรุนแรงอื่นที่อาจนำไปสู่การตอบโต้ในระดับนโยบายหรือเวทีระหว่างประเทศ

▍เหตุผลที่ข้อเสนอของนายกรัฐมนตรีไม่สอดคล้องกับแนวทาง “พอเหมาะ”

1. ลดทอนอำนาจต่อรองของไทย:

การเปิด-ปิดด่านให้ตรงกันจะทำให้ไทยสูญเสียเครื่องมือสำคัญในการเจรจาต่อรอง โดยเฉพาะในช่วงที่จำเป็นต้องส่งสัญญาณกดดันหรือแสดงความไม่พอใจทางการเมือง

2. บั่นทอนมาตรการทางยุทธศาสตร์ที่ฝ่ายความมั่นคงใช้:

มาตรการไม่ตรงเวลาเป็นกลไกเชิงนโยบายที่ใช้อย่างต่อเนื่องในการตอบสนองต่อพฤติกรรมที่ไม่เป็นมิตรของกัมพูชา เช่น การเสริมกำลังในพื้นที่พิพาท หรือการเคลื่อนไหวเชิงสัญลักษณ์ที่กระทบต่ออธิปไตย

3. ละเลยมิติยุทธศาสตร์และความมั่นคง:

แม้นายกรัฐมนตรีจะให้เหตุผลในเชิงการค้าและประชาชน แต่ข้อเสนอดังกล่าวไม่ได้คำนึงถึงมิติยุทธศาสตร์ที่ลึกกว่าการอำนวยความสะดวกในระยะสั้น ซึ่งเป็นหัวใจของการใช้มาตรการ “พอเหมาะ” อย่างมีประสิทธิภาพ

4. ขัดกับสถานการณ์ปัจจุบันของพื้นที่:

หน่วยงานความมั่นคงรายงานว่า ชายแดนบางจุดมีความเสี่ยงจากการเปลี่ยนแปลงที่มั่นและการเคลื่อนไหวของกัมพูชา จึงจำเป็นต้องใช้มาตรการควบคุมเวลาเป็นกลไกกดดันเชิงยุทธศาสตร์

▍ข้อสรุป

ข้อเสนอของนายกรัฐมนตรีในการให้เวลาเปิด-ปิดด่านตรงกันกับกัมพูชา แม้มีเจตนาดีในการอำนวยความสะดวกแก่ประชาชนและการค้า แต่ ไม่สอดคล้องกับแนวทาง “มาตรการแข็งกร้าวที่พอเหมาะ” ที่ฝ่ายความมั่นคงและนักยุทธศาสตร์ใช้ในการบริหารความสัมพันธ์ชายแดน

การกำหนดเวลาเปิด-ปิดไม่ตรงกันคือเครื่องมือที่ไทยใช้ในระดับ “พอเหมาะ” เพื่อกดดันอีกฝ่ายโดยไม่ยกระดับความขัดแย้ง เป็นการรักษาความได้เปรียบของไทยในสถานการณ์พิพาท และหากยกเลิกมาตรการนี้ ไทยอาจ สูญเสียเครื่องมือต่อรองสำคัญในช่วงเวลาที่จำเป็นต้องรักษาอำนาจและเสถียรภาพเชิงยุทธศาสตร์

▍การใช้เวลาเปิด–ปิดด่านเป็นกลไกเชิงยุทธศาสตร์: กรณีศึกษาภายใต้กรอบ Coercive Diplomacy

ในทางรัฐศาสตร์และยุทธศาสตร์ความมั่นคง การเลือกใช้มาตรการที่ไม่รุนแรง แต่มีผลต่อพฤติกรรมของรัฐคู่ขัดแย้งนั้น เข้าข่ายแนวคิด “Coercive Diplomacy” หรือ “การทูตแบบกดดัน” (George, 1991) ซึ่งหมายถึง การใช้อิทธิพลทางเศรษฐกิจ การทหาร หรือโครงสร้าง เพื่อ กดดันให้อีกฝ่ายเปลี่ยนพฤติกรรม โดยไม่ต้องใช้กำลังทหารโดยตรง

▍การกำหนดเวลาเปิด–ปิดด่านชายแดนไม่ตรงกัน: ตัวอย่างของ “การกดดันที่มีเป้าหมายจำกัด” (Limited Coercive Objective)

กรณีที่ไทยกำหนดเวลาเปิด–ปิดด่านชายแดนให้ “ไม่ตรงกัน” กับกัมพูชา ถือเป็นหนึ่งในมาตรการ Low-Intensity Coercion ที่มุ่งกดดันโดยอาศัย โครงสร้างความเหนือกว่าทางภูมิรัฐศาสตร์และระบบโลจิสติกส์ ของไทยที่กัมพูชาพึ่งพา เช่น ไฟฟ้า การค้าชายแดน และแรงงาน โดยไม่ใช้ความรุนแรงหรือขัดหลักกฎหมายระหว่างประเทศ

ในบริบทนี้:

• ไทยใช้ข้อได้เปรียบทางภูมิศาสตร์ในการ “บีบคอขวด” ด้านเวลาและระบบโลจิสติกส์เพื่อสร้าง “Pain Points” ให้เกิดขึ้นในระดับที่อีกฝ่ายต้องหาทางเจรจา

• การไม่เปิดด่านพร้อมกันส่งผลต่อ ค่าใช้จ่ายแฝง (transaction costs) และความไม่แน่นอนในการค้าข้ามแดน ซึ่งเพิ่มแรงกดดันภายในกัมพูชา

• มาตรการนี้สามารถ “ผ่อนหรือยกระดับ” ได้ตามพฤติกรรมของอีกฝ่าย จึงมี ความยืดหยุ่นเชิงยุทธศาสตร์ (Strategic Flexibility) สูง

→ Thomas Schelling (1966) เคยระบุว่า “The power to hurt is bargaining power.” การสร้างต้นทุนให้คู่ขัดแย้งต้องแบกรับ ยิ่งทำให้ท่าทีต่อรองมีน้ำหนักมากขึ้น โดยไม่ต้องยิงปืนแม้แต่นัดเดียว

▍ข้อเสนอของนายกรัฐมนตรีกับแนวคิด “ความชอบธรรมทางปกครอง” (Legitimacy vs Strategic Leverage)

แม้ข้อเสนอของนายกรัฐมนตรีที่ให้เวลาเปิด–ปิดด่านตรงกันจะดู เป็นมิตรและส่งเสริมภาพลักษณ์รัฐบาลในด้านประชาชน–การค้า แต่ในเชิงทฤษฎีอาจเข้าข่าย “การลดระดับอำนาจต่อรองของรัฐโดยไม่จำเป็น” ซึ่งเสี่ยงต่อการสูญเสีย leverage (คานงัด) ที่สำคัญในสถานการณ์พิพาท

• ในทางรัฐศาสตร์ แนวคิดเรื่อง Strategic Hedging หรือ “การสร้างทางเลือกเพื่อถ่วงดุล” (Kuik, 2008) เน้นว่ารัฐควรสงวนกลไกที่ใช้กดดันไว้ในยามจำเป็น ไม่ใช่สละเครื่องมือต่อรองล่วงหน้าเพียงเพื่อลดความอึดอัดชั่วคราว

• หากถอดมาตรการ “เปิด–ปิดด่านไม่ตรง” โดยไม่มีมาตรการทดแทน ไทยอาจ สูญเสียพื้นที่ยุทธศาสตร์ทางการทูต ที่ไม่สามารถเรียกคืนได้ง่าย

▍ข้อสังเกตเชิงทฤษฎี: จาก Soft Power สู่ Smart Power

ในบริบทนี้ การควบคุมเวลาเปิด–ปิดด่านอาจไม่ใช่ “อำนาจแข็ง” (Hard Power) แบบดั้งเดิม แต่ก็ไม่ใช่ “อำนาจอ่อน” (Soft Power) เช่นกัน หากแต่เข้าใกล้แนวคิด Smart Power – การผสมผสานระหว่างการชักจูงและการกดดันอย่างชาญฉลาด (Nye, 2009)

→ การใช้มาตรการแข็งกร้าวที่ “พอเหมาะ” เช่นนี้ จึงเป็นตัวอย่างของ Smart Power in Border Diplomacy ซึ่งควรได้รับการรักษาไว้ในกรอบยุทธศาสตร์ระยะยาว

Strategic Missteps or Misunderstood Diplomacy?

#EddieAtsadang #DecodingPowerGames #CambodiaResponse

Thailand’s Passive Approach Toward Cambodia Raises Questions About Sovereignty and Leverage

The growing dissatisfaction among Thai citizens over the government’s “defensive posture” toward Cambodia — coupled with increasing public calls for a tougher stance — reflects a deep sense of nationalism and concern for the country’s sovereign dignity. Such reactions are not uncommon in situations involving border disputes. However, any decision to adopt a more assertive or restrained approach should be grounded in national strategy, long-term interests, and a careful assessment of the multidimensional consequences.

In the realm of political science and security strategy, the use of non-violent yet behavior-influencing tools aligns with the concept of “Coercive Diplomacy” (George, 1991). This approach entails applying economic, military, or structural pressure to induce a change in the adversary’s behavior—without resorting to direct military action.

Thailand’s use of mismatched border gate opening hours is an example of a calibrated, non-escalatory tool aimed at applying pressure while maintaining strategic advantage. It represents a subtle yet effective mechanism within the framework of coercive diplomacy.

However, the Prime Minister’s recent proposal to synchronize gate operation times with Cambodia may lead to the unilateral dismantling of one of Thailand’s key bargaining tools—a strategic leverage point that has served the nation’s interests without escalating tensions.

Why would the Prime Minister propose a move that compromises Thailand’s strategic leverage?

One possible answer lies in a misunderstanding between “strategic moderation” and “unnecessary concession.” The current administration appears to favor a soft foreign policy that emphasizes diplomatic harmony over maintaining coercive instruments. This may stem from a failure to recognize that strategic pressure is not the same as aggression—it is a means of preserving leverage without provoking conflict.

Unconditionally relinquishing a pressure tactic without securing any reciprocal concession from the opposing party may reflect a lack of understanding of the principle of reciprocity, a cornerstone of power-based diplomacy. Worse still, transforming a strategic instrument of coercive diplomacy into a “symbolic concession” only emboldens the other side, weakening Thailand’s hand at the negotiating table.

Alternatively, the Prime Minister’s decision may have been influenced by domestic political considerations—a need to signal goodwill to domestic interest groups who benefit from border trade and may favor smoother cross-border operations. This dynamic aligns with Robert Putnam’s “Two-Level Game” theory (1988), which explains how foreign policy decisions are often shaped by internal political pressures and interest group alignments.

In either case, the move risks undermining Thailand’s strategic sovereignty—the ability to make independent decisions based on national interest and to retain leverage in asymmetric negotiations. At a time when assertiveness and strategic clarity are needed, stepping back without a deal on the table may be not only premature, but perilous.

Thai Dissatisfaction with Defensive Measures and the Strategic Call for Firm Action Against Cambodia

▍Advantages of Applying Firm Measures

- Enhanced Bargaining Power: Targeted actions such as restricting border trade, suspending cooperation projects, or limiting electricity and internet access can pressure Cambodia into negotiations with a more conciliatory stance.

- Affirmation of Sovereignty: Demonstrates to the Thai public that the government is resolute and responsive to threats against national dignity.

- Leverage of Asymmetries: Cambodia continues to rely on Thailand for energy, trade, and labor—an advantage that can be tactically employed.

▍Risks and Limitations of Hardline Policies

- Escalatory Retaliation: Cambodia may reciprocate with similar or escalated countermeasures, such as border closures, appeals to international forums, or nationalist mobilization.

- Harm to Border Communities: Disruptions in cross-border trade and employment could severely impact livelihoods on both sides.

- International Image Costs: Thailand’s measures could be misinterpreted as excessive or contrary to norms of peaceful conflict resolution.

- Domestic Political Blowback: Opposition groups might exploit hardline measures to portray the government as impulsive or strategically short-sighted.

▍The Strategic Alternative: Calibrated Defensive Posture

Despite domestic pressure, most experts advocate a “strategically calibrated defensive strategy” — emphasizing bilateral mechanisms and diplomatic engagement, while preparing contingent countermeasures should the situation deteriorate.

▍What Constitutes “Calibrated Firmness”?

“Calibrated” in this context implies the application of forceful measures only to the extent necessary to maintain leverage without provoking uncontrolled escalation. It means making the opponent uncomfortable enough to seek resolution, but not cornered into confrontation.

▍Key Features of Calibrated Measures

- Clear Objective: Focused on deterrence, not political grandstanding or emotional responses.

- Selective Pressure Points: For instance, trade categories, security inspections, or specific infrastructure cooperation delays.

- Built-in Flexibility: Designed to scale up or down depending on reciprocal signals.

- Avoid Civilian Harm: Measures should minimize damage to long-term bilateral relationships or civilian well-being.

- Sophisticated Signaling: Emphasizes quiet diplomacy, controlled messaging, and strategic signaling at international venues.

▍Examples of Calibrated Firmness

- Limited adjustment of border checkpoint opening hours

- Tightened customs inspections on cross-border goods

- Temporary visa restrictions for specific categories

- Suspension of joint development programs

- Diplomatic signaling with embedded conditions for resuming cooperation

▍Policy Friction: Border Checkpoint Timing Dispute

Prime Minister Paetongtarn Shinawatra recently proposed aligning Thai–Cambodian border checkpoint hours to facilitate trade and cross-border mobility. However, this suggestion clashes with the stance of Thai security officials, who argue that asynchronous checkpoint hours serve as a strategic lever to exert pressure in times of heightened tension.

▍Checkpoint Timing as a Case of “Limited Coercive Objective”

Maintaining misaligned border timings is a classic case of low-intensity coercion—leveraging logistical asymmetries to induce negotiation without overt aggression. This approach fits within the framework of Coercive Diplomacy, defined by Alexander George (1991) as “the use of threats and limited force to influence an adversary’s behavior without full-scale military confrontation.”

Thailand’s strategy includes:

- Chokepoint Control: Leveraging its geographic and logistical superiority to create friction points.

- Raising Transaction Costs: Introducing delays and uncertainties that pressure Cambodia internally.

- Strategic Flexibility: Easily adjustable in response to behavioral shifts, maintaining adaptability without permanent escalation.

As Thomas Schelling (1966) put it: “The power to hurt is bargaining power.” Inflicting manageable costs strengthens negotiating positions—often without firing a single shot.

▍Strategic Misalignment: PM’s Proposal vs. National Security Logic

While well-intentioned, the Prime Minister’s proposal may inadvertently:

- Weaken Thailand’s Leverage: Synchronizing checkpoint hours eliminates a vital pressure tool.

- Undermine Security Protocols: Discards a longstanding policy used to respond to Cambodian provocations.

- Overlook Strategic Dimensions: Emphasizes convenience over long-term strategic positioning.

- Contradict On-the-Ground Realities: Security agencies cite increasing risks in disputed zones, necessitating control over temporal dynamics.

▍Border Diplomacy under Smart Power

The manipulation of border checkpoint hours is neither classic Hard Power nor mere Soft Power. It closely resembles Smart Power — a concept coined by Joseph Nye (2009) — which blends coercion with persuasion to achieve strategic outcomes. Calibrated firmness in border diplomacy exemplifies Smart Power, allowing Thailand to exert influence without overstepping legal or ethical boundaries.

▍Conclusion

While Thailand faces legitimate pressure to respond decisively, strategic patience coupled with calculated firmness offers a more sustainable path. Preserving leverage through limited coercive tools—such as control over checkpoint timings—is essential for safeguarding national interests without inviting unnecessary escalation.

The Prime Minister’s proposal, though aligned with trade facilitation and humanitarian intent, inadvertently undermines one of Thailand’s key tools in asymmetric diplomacy. In strategic terms, not everything that appears conciliatory is wise, and not every form of pressure is belligerent. The key lies in balance—firm, flexible, and forward-looking.

▍References

- George, A. L. (1991). Forceful Persuasion: Coercive Diplomacy as an Alternative to War. United States Institute of Peace.

- Schelling, T. C. (1966). Arms and Influence. Yale University Press.

- Nye, J. S. (2009). The Future of Power. Public Affairs.

- Kuik, C. C. (2008). The Essence of Hedging: Malaysia and Singapore’s Response to a Rising China. Contemporary Southeast Asia.